Update January 13, 2025:

I would like to briefly clarify a topic that has been discussed more frequently:

I am not referring to the general transfer of data to AWS or Facebook, but to the transfer of personal data to companies in a third country without appropriate protective measures, especially when it’s transferred by a public body that should be held to the highest standards.

When I log in to Facebook to read, like or write posts, I have full control over this and can decide for myself which data is transferred to third countries without appropriate safeguards. I can use anonymization services when surfing the Internet and/or regularly delete cookies to reduce my digital footprint.

When I visited the page on the future of Europe, I did not have this option or assumed that appropriate protective measures were in place in accordance with the legal requirements.

The fact that EUCOM has such negotiating power has since been demonstrated by the Microsoft ILA, which was probably closed in 2021. Whether and in what form this has happened with AWS and/or Meta/Facebook is not known to me. As can be seen below, as a user, I trusted that corresponding agreements or technical solutions were in place, as EUKOM in particular should set an example here.

—

The judgment T-354/22 Bindl / Commission was published yesterday, and due to its length, I have not been able to analyze it in detail yet. Nevertheless, I would like to provide some initial feedback:

I am satisfied with the judgment, even though it surprised me in some aspects. I would particularly like to highlight two points that were decisive reasons for the lawsuit:

- A transfer to a third country without appropriate safeguards is a violation of data protection regulations.

- The uncertainty accompanying the unlawful transfer of data constitutes damage.

Two issues in the rather lengthy judgment (202 paragraphs) may require further context or explanation due to technical aspects:

Amazon Web Services (AWS) Request to Servers in the USA (Paragraph 119)

It is correct that requests were routed to various AWS Cloudfront servers, including in the USA, in close temporal proximity. It is also true that we stated this was due to settings on my device, which have data protection-related reasons. Allow me to elaborate briefly:

The internet operates based on the communication of devices through IP addresses (e.g., 10.1.2.3), while users typically only enter domain names (e.g., eugd.org), which are then translated into IP addresses by nameservers, functioning like a „phonebook“.

These nameservers are generally operated by internet providers (e.g., Telekom, Vodafone) and are provided free of charge.

When using public Wi-Fi, nameservers are typically provided by the Wi-Fi provider, such as a hotel, café, train, or public Wi-Fi operators. In such situations, the use of VPNs is often recommended to prevent data from being read by the Wi-Fi provider. Unfortunately, many public Wi-Fi providers block VPN services, making secure transmission via SSL („https“ before the domain) essential.

Additionally, providers control nameservers and may either provide incorrect responses from the „phonebook,“ potentially leading to manipulated websites, or log all requests, enabling the creation of detailed profiles, especially if the Wi-Fi is used for more than a few minutes. Every domain visit, whether google.com or an emotional support service, can be logged.

To prevent this, I regularly use multiple nameservers that automatically alternate, primarily those operated by public institutions (e.g., universities) that claim not to store data or my German internet provider, which is subject to strict legal requirements.

Given this, it can influence the functioning of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) like AWS Cloudfront. Contrary to common belief, these networks do not necessarily operate based on proximity to the user’s location but rather the nameserver’s location. For instance, if a nameserver requests an IP address from Amazon for „futureu.europa.eu,“ Amazon responds based on the nameserver’s location. If Amazon believes the nameserver is in Munich, it provides an AWS server IP in Munich; if it believes the nameserver is in the USA, it provides an AWS server IP in the USA. This is likely what happened in this case. However, confirming this would require clarification by the Commission and/or AWS.

Why the Future of Europe website must also be consistently accessible from the USA remains unclear to me and does not seem absolutely necessary. Using servers exclusively within the EU, which also offer high reliability, would have avoided the issue of direct transmission to the USA entirely.

During the hearing, one of the judges even raised the question of whether using TOR, an anonymization service, could result in personal data being transferred to the USA. This is indeed the case, as it is with VPN services, which can be used to increase user data security.

Overall, based on an initial analysis, we are not convinced by this aspect and will examine how to proceed.

Use of the „Facebook Login“ Service

It is undisputed that I clicked on the link for Facebook Login and was then redirected to Facebook’s page, where personal data was processed. This is generally acceptable but must be viewed in context:

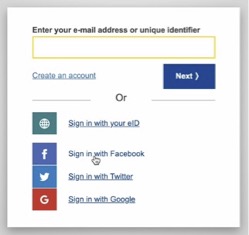

The Commission, as the website operator, offered various login options (screenshot from June 2022):

Besides eID, Facebook, Twitter, and Google were available, but not options like netID or a „single-use link,“ which would likely be less intrusive from a data protection perspective.

Since Facebook was displayed as the first third-party option (not alphabetically sorted), I saw this as a preference by the Commission. There was no indication that clicking this link would directly transfer data (of the page where one intended to log in) to Facebook, nor were there any notes about data transfers to the USA. Therefore, I assumed SCCs and „additional measures“ were in place, as there was no adequacy decision at that time. While I understood that such „additional measures“ are challenging, I hoped the EU Commission would have used its considerable negotiating power to ensure the service was legally compliant.

However, during subsequent communication about the request for information and the lawsuit, it became apparent that this was not the case and that the transfer likely occurred without any SCCs.

Accordingly, if one interprets it this way, I contributed to the transfer myself, albeit in trust that the website only offers legally compliant services. That this was not the case only became clear weeks or months after the „click.“

Central Question

Can users of a website trust that it is designed to comply with data protection regulations, or must they know its technical and legal functionality in detail to use it lawfully, as a single wrong click can lead to unintended data disclosure?

We will thoroughly review how to proceed in the coming days, and no decision has been made yet.

Many thanks at this point to Tilman Herbrich, Peter Hense, and Christian Däuble from the law firm Spirit Legal for their excellent work!